Ecuador

Ecuador’s Correa Breezes to 2nd Re-election

By AP / Gabriela Molina and Gonzalo SolanoFeb. 17, 2013Add a Comment

Ecuador’s Correa Breezes to 2nd Re-election

By AP / Gabriela Molina and Gonzalo SolanoFeb. 17, 2013Add a Comment

Follow @TIMEWorld

(QUITO, Ecuador) — President Rafael Correa, a dynamic leftist who has championed Ecuador’s lower classes with generous social spending but faced wide rebuke as intolerant of dissent, coasted to a second re-election on Sunday.

Correa won 56.7 percent of the vote against 24 percent for his closest challenger, former Banco de Guayaquil chief Guillermo Lasso, with 36 percent of the vote counted.

So confident was Correa of victory that he appeared on state TV less than an hour after polls closed, hugging jubilant supporters at the Carondelet presidential palace.

(MORE: Correa’s Clemency: Why Critics Say Ecuador’s President Is Still a Threat to Press Freedom)

He then addressed a cheering crowd from its balcony.

“This victory is yours. It belongs to our families, our wives, our friends and neighbors, the entire nation,” Correa said. “We are only here to serve you. Nothing for us. Everything for you, a people who have become dignified in being free.”

Lasso conceded as first official results were released, congratulating Correa for “a victory deserving respect.” Former President Lucio Gutierrez won 5.9 percent. The rest of the vote was divided among five other candidates.

Correa told reporters his goal is to now further reduce poverty, which the United Nations says dropped from 37.1 percent to 32.4 percent since he first took office in 2007, as he deepens what he terms his “citizens’ revolution.”

Correa, 48, has brought uncharacteristic political stability and modest economic growth to this oil-exporting nation of 14.6 million people that cycled through seven presidents in the decade before him.

He has raised living standards for the poor and widened the welfare state with region-leading social spending, though human rights groups say he bullies anyone who gets in his way and civil liberties have suffered.

Correa’s result Sunday topped his April 2009 re-election, when he won 51.7 percent of the vote. That election was mandated by a constitutional rewrite approved in a referendum. Correa is legally barred from another 4-year term — unless he seeks to amend the constitution.

A champion of big government in the mold of Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez but more respectful of private property, Correa has made public education and health care more accessible, built or improved 7,820 kilometers (4,870 miles) of highways and, the government says, created 95,400 jobs in the past four years.

Lasso had promised a government friendlier to foreign investment, lower taxes on job-creating companies and a rolling back of elements of what Correa calls his “21st century socialism,” such as a 5 percent tax on capital removed from Ecuador.

Among voters casting their ballot for Correa in Quito was Jomaira Espinosa, 18.

“Before (Correa), my family didn’t have enough to eat” and her father couldn’t find work, she said. Now her father has a job as a public servant and she expects to be able to study for free at a university thanks to Correa’s programs.

But Correa has also arbitrarily wielded a near-monopoly on state power, critics say, using criminal libel law against opposition news media and seizing the country’s airwaves several times a week to spread his political gospel and attack opponents.

German Calapucha, a 29-year-old accountant, said he voted against Correa because he’s tired of the president’s imperiousness.

“He thinks that because he wins elections he has the right to mistreat people,” Calapucha said. “I want a country where people respect each other.”

Correa has eroded the influence of opposition parties, the Roman Catholic Church and the news media and used criminal libel law to try to silence opposition journalists. Critics lament his staking of courts with friendly judges and the government’s prosecution of indigenous leaders for organizing protests against Correa’s opening up of Ecuador to large-scale mining without their consent.

“He is far too insolent and I want there to be freedom of expression,” said Laura Realpe, a 59-year-old housewife.

One blessing for Correa has been oil prices that have been hovering around $100 a barrel.

Petroleum accounts for more than half of Ecuador’s export earnings and have allowed it to lead the region in 2011 in public spending as a portion of gross domestic product at 11.1 percent, according to the United Nations. Bolivia was second with 10.8 percent.

Voters such as Fabian Garzon, a 48-year-old messenger and cleaner, credit Correa with improving their lives.

Garzon has what he’s always dreamed of: his own apartment, which he is buying with a $24,000 government-issued mortgage. His monthly salary, meanwhile, has more than doubled over the past four years, from $200 to $450, and payments for his social security, vacation and other government-mandated contributions are being made regularly.

(MORE: “Ecuador’s Correa Wins Another Libel Case: Are the Latin American Media Being Bullied?”)

“I worked 25 years without having my own house and at this age, thank God, I’m able to own my own home,” Garzon said.

In all, 1.9 million people receive $50 a month in aid from the state. Critics complain that the popular handouts to single mothers, needy families and the elderly poor, along with other subsidies, have bloated the government.

The number of people working for the government has burgeoned from 16,000 to 90,000 during Correa’s current term, Ecuador’s nongovernmental Observatory of Fiscal Policy said in a December report.

Correa also has been unable to stop a growing sensation of vulnerability in a country where robberies and burglaries grew 30 percent in 2012 compared with the previous year.

The graduate of the University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign gained an early reputation as a maverick, defying international financiers by defaulting on $3.9 billion in foreign debt obligations and rewriting contracts with oil multinationals to secure a higher share of oil revenues for Ecuador.

He has also kept the United States at arm’s length while upsetting Britain and Sweden in August by granting asylum at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, the online spiller of leaked U.S. government secrets who is wanted for questioning in Sweden for alleged sexual assault.

Correa has cozied up to U.S. rivals Iran and China. The latter is the biggest buyer of Ecuador’s oil and holds $3.4 billion in Ecuadorean debt, Finance Minister Patricio Rivera says.

Correa won 56.7 percent of the vote against 24 percent for his closest challenger, former Banco de Guayaquil chief Guillermo Lasso, with 36 percent of the vote counted.

So confident was Correa of victory that he appeared on state TV less than an hour after polls closed, hugging jubilant supporters at the Carondelet presidential palace.

(MORE: Correa’s Clemency: Why Critics Say Ecuador’s President Is Still a Threat to Press Freedom)

He then addressed a cheering crowd from its balcony.

“This victory is yours. It belongs to our families, our wives, our friends and neighbors, the entire nation,” Correa said. “We are only here to serve you. Nothing for us. Everything for you, a people who have become dignified in being free.”

Lasso conceded as first official results were released, congratulating Correa for “a victory deserving respect.” Former President Lucio Gutierrez won 5.9 percent. The rest of the vote was divided among five other candidates.

Correa told reporters his goal is to now further reduce poverty, which the United Nations says dropped from 37.1 percent to 32.4 percent since he first took office in 2007, as he deepens what he terms his “citizens’ revolution.”

Correa, 48, has brought uncharacteristic political stability and modest economic growth to this oil-exporting nation of 14.6 million people that cycled through seven presidents in the decade before him.

He has raised living standards for the poor and widened the welfare state with region-leading social spending, though human rights groups say he bullies anyone who gets in his way and civil liberties have suffered.

Correa’s result Sunday topped his April 2009 re-election, when he won 51.7 percent of the vote. That election was mandated by a constitutional rewrite approved in a referendum. Correa is legally barred from another 4-year term — unless he seeks to amend the constitution.

A champion of big government in the mold of Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez but more respectful of private property, Correa has made public education and health care more accessible, built or improved 7,820 kilometers (4,870 miles) of highways and, the government says, created 95,400 jobs in the past four years.

Lasso had promised a government friendlier to foreign investment, lower taxes on job-creating companies and a rolling back of elements of what Correa calls his “21st century socialism,” such as a 5 percent tax on capital removed from Ecuador.

Among voters casting their ballot for Correa in Quito was Jomaira Espinosa, 18.

“Before (Correa), my family didn’t have enough to eat” and her father couldn’t find work, she said. Now her father has a job as a public servant and she expects to be able to study for free at a university thanks to Correa’s programs.

But Correa has also arbitrarily wielded a near-monopoly on state power, critics say, using criminal libel law against opposition news media and seizing the country’s airwaves several times a week to spread his political gospel and attack opponents.

German Calapucha, a 29-year-old accountant, said he voted against Correa because he’s tired of the president’s imperiousness.

“He thinks that because he wins elections he has the right to mistreat people,” Calapucha said. “I want a country where people respect each other.”

Correa has eroded the influence of opposition parties, the Roman Catholic Church and the news media and used criminal libel law to try to silence opposition journalists. Critics lament his staking of courts with friendly judges and the government’s prosecution of indigenous leaders for organizing protests against Correa’s opening up of Ecuador to large-scale mining without their consent.

“He is far too insolent and I want there to be freedom of expression,” said Laura Realpe, a 59-year-old housewife.

One blessing for Correa has been oil prices that have been hovering around $100 a barrel.

Petroleum accounts for more than half of Ecuador’s export earnings and have allowed it to lead the region in 2011 in public spending as a portion of gross domestic product at 11.1 percent, according to the United Nations. Bolivia was second with 10.8 percent.

Voters such as Fabian Garzon, a 48-year-old messenger and cleaner, credit Correa with improving their lives.

Garzon has what he’s always dreamed of: his own apartment, which he is buying with a $24,000 government-issued mortgage. His monthly salary, meanwhile, has more than doubled over the past four years, from $200 to $450, and payments for his social security, vacation and other government-mandated contributions are being made regularly.

(MORE: “Ecuador’s Correa Wins Another Libel Case: Are the Latin American Media Being Bullied?”)

“I worked 25 years without having my own house and at this age, thank God, I’m able to own my own home,” Garzon said.

In all, 1.9 million people receive $50 a month in aid from the state. Critics complain that the popular handouts to single mothers, needy families and the elderly poor, along with other subsidies, have bloated the government.

The number of people working for the government has burgeoned from 16,000 to 90,000 during Correa’s current term, Ecuador’s nongovernmental Observatory of Fiscal Policy said in a December report.

Correa also has been unable to stop a growing sensation of vulnerability in a country where robberies and burglaries grew 30 percent in 2012 compared with the previous year.

The graduate of the University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign gained an early reputation as a maverick, defying international financiers by defaulting on $3.9 billion in foreign debt obligations and rewriting contracts with oil multinationals to secure a higher share of oil revenues for Ecuador.

He has also kept the United States at arm’s length while upsetting Britain and Sweden in August by granting asylum at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, the online spiller of leaked U.S. government secrets who is wanted for questioning in Sweden for alleged sexual assault.

Correa has cozied up to U.S. rivals Iran and China. The latter is the biggest buyer of Ecuador’s oil and holds $3.4 billion in Ecuadorean debt, Finance Minister Patricio Rivera says.

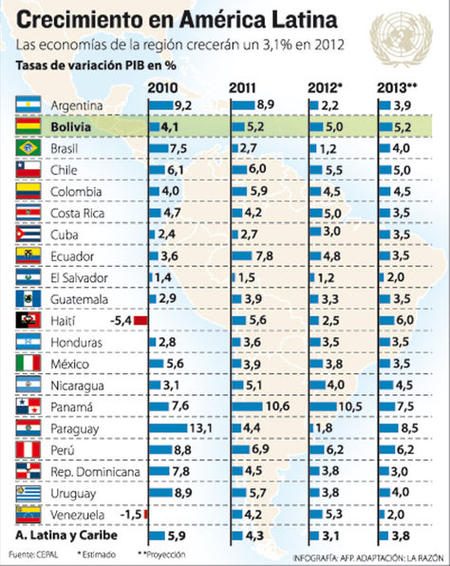

Credit: :La RazónIn contrast, despite the worldwide economic crisis, Bolivia’s economy is on track to increase by

Credit: :La RazónIn contrast, despite the worldwide economic crisis, Bolivia’s economy is on track to increase by  El Alto market. Credit: gulfnews.com

El Alto market. Credit: gulfnews.com

Comment